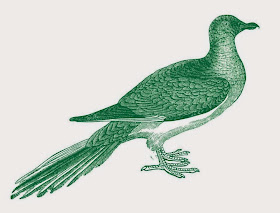

A century ago this fall, the world’s last passenger pigeon, a bird named Martha, died at the Cincinnati Zoo. Her death marked the end of an astonishing decline in that bird’s numbers; in America’s first centuries, passenger pigeons were so abundant that stories about them can be almost impossible to believe. Cotton Mather described a flock a mile wide that took hours to pass overhead, and John James Audubon reported that they blocked out the sun like an eclipse.

By 1900, thanks to deforestation and overhunting, passenger pigeons had disappeared from the wild. Martha’s 1914 death in captivity marked not just the end of what had been the most common bird in the country. It was also the beginning of widespread public awareness of the problem of extinction.

Once, the idea that animals would go extinct was unthinkable; it was believed that the world was a certain way and always would be. But the drastic dwindling of the American buffalo and a handful of high-profile extinctions, including the colorful Carolina parakeet just a few years after Martha’s death, made the permanent loss of a familiar animal a key way we think about damage to our world. Since then, extinction has become one of the most powerful illustrations of the human effect on the planet.

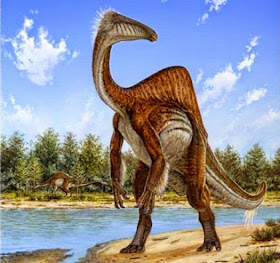

Today the threat of extinction is one of the most motivating factors for environmental activism. Endangered animals including pandas and tigers serve as logos for many conservation groups. Leonardo DiCaprio, who has donated millions to protect animals including tigers and elephants, told the audience at a gala in July, “Not since the age of the dinosaurs have so many species of plants and animals become extinct in such a short period of time.” The party raised $25 million.

Extinction’s emotional power is rooted not just in the sense of loss—the idea that a familiar animal will be unknown to our children—but in how black and white it is: The animal is either still with us, or gone forever. But in recent years, extinction itself has become a hotly argued topic among scientists who study the natural world. A high-profile paper a few years ago said the rate of new extinctions was much lower than estimates; this summer, another said it was far higher. Extinction, it turns out, is extremely hard to document, and the health of species and the planet is much more complex than the binary “extinct” or “not extinct.”

As scientists debate numbers and definitions, it has triggered another fight, one about how the argument will affect the public. Most scientists in this field are also strong conservationists, and many of them worry that airing dirty laundry—even arguments about percentages—could hurt the cause. Others worry that there’s more to lose by burying those doubts.

“There have certainly been some enormous exaggerations,” said Richard Ladle, a Brazil-based conservation scientist who studies extinction. “If you keep on talking about very, very large figures and nothing appears to be happening, eventually that’s going to erode public confidence in conservation science.”

Such is the economy of nature, that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct,” Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1784. A fossil collector himself, he told Lewis and Clark to keep a sharp eye out for mammoths on their explorations. Mark V. Barrow Jr., a historian at Virginia Tech, says that Westerners of Jefferson’s era believed the natural world to be orderly, young, and static, just the way God created it. In that context, “extinction was unthinkable,” explained Barrow, the author of the 2009 book “Nature’s Ghosts: Confronting Extinction from the Age of Jefferson to the Age of Ecology.”

By the early 19th century, the existence of extinction had been accepted by most scientists, and over the next 200 years it gradually became a public concern, as it became clear that human beings were playing an active role in making it happen. Martha’s death helped inspire the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty, a multinational protection agreement; President Nixon’s signing of the Endangered Species Act in 1973 was a high point of public and political engagement on the problem.

Since then, pronouncements from conservation advocates have grown more and more dire. In 1979, Berkeley ecologist Norman Myers published a book called “The Sinking Ark,” which claimed 40,000 species were disappearing each year. The next decade, a biologist who worked for the World Wildlife Fund predicted up to 20 percent of all species would disappear by the turn of the millennium. That didn’t happen, but the drumbeat of alarms continues: A much-publicized paper in 2004 warned that by 2050, climate change could put 1 million species at risk of extinction.

There’s at least one problem with these predictions: Where are the bodies? Actual documented extinctions are vanishingly rare. “If you ask any member of the public to name 10 species that have gone extinct in the last century, most would really really struggle,” Ladle said. “Then you’ve got the world’s most famous conservationists telling you that 27,000 are going extinct every year. The two don’t tally up.” The International Union for Conservation of Nature, which keeps the most definitive list of extinct and threatened species, has counted just over 800 total confirmed animal extinctions since the year 1600.

That disconnect illuminates one reason Martha’s death drew so much attention: Unlike most extinctions, it was one documented in the moment. “Extinction is really about knowing the last individual is gone, and we don’t monitor the life of the planet that accurately,” said Stephen Hubbell, an ecologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. “We have to use approximations, and that’s where the argument comes in.”

About 1.5 million plant and animal species have been named, but estimates of how many actually exist vary from 2 million to 100 million. Those numbers change every year: New species are discovered, and others wink out of existence, often without us ever knowing they were there at all. So when scientists talk about thousands of species going extinct in a year, they aren’t counting disappearances: They’re making extrapolations based on estimates of habitat loss, and of how many species currently exist, and how many have existed in history.

In 2011, Hubbell coauthored a controversial paper that was published in the journal Nature under the bold title “Species-area relationships always overestimate extinction rates from habitat loss.” It was a technical argument that questioned an equation commonly used to estimate extinction, but the implications were clear: Conservationists really had no idea what the extinction rate is, and were likely overstating their case. That notion had been bubbling up for several years; an earlier paper by two tropical biologists claimed that population shifts and forest regrowth would mean rain-forest extinctions would be lower than many predictions.

The critiques by Hubbell and others have not been well received by some conservationists. “They’re either venal or stupid,” said Stuart Pimm, a leading extinction expert, of those who question the higher estimates. Pimm, the Doris Duke Professor of Conservation Ecology at the Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University, published a paper this summer warning that species are currently dying off at 1,000 times the rate they were before the human era, and in the future are likely to perish at 10,000 times that rate. “The rates are the rates,” Pimm said. “Those numbers aren’t unnecessarily alarmist; they’re the best numbers we can get our hands on.”

Why does the exact extinction rate matter? In part, it’s because animal and plant extinctions are a bellwether for broader environmental problems that could have an impact on humans, too. It’s also a way to track the loss of biological richness—not just the beauty of nature, but the potentially crucial and undiscovered resources its species contain. And if we’re asking people to modify their behavior to support animal survival, it seems logical that we would want to know whether it’s working. As Robert May, a leading extinction-rate expert, has put it, “If we are to meet the challenges facing tomorrow’s world, we need a clearer understanding of how many species there are.”

The huge numbers of extinctions being thrown around may be overstated, or they may be understated. They may also, some say, be the wrong thing entirely to focus on. “It bothers me, and you can quote me on this, that we are still talking about species-level extinction,” said Ross MacPhee, a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural History who studies extinction. There are other vital questions: Is there a wild population diverse enough to be healthy? Does the animal exist only in zoos? Is a threatened species a linchpin in a large ecosystem? Is it particularly unusual genetically? As Ladle pointed out in a 2010 paper, “extinction” isn’t as binary as it seems: There’s local extinction, extinction in the wild, extinction of subspecies, theoretical extinction of unknown species, and so on—each of which can grab headlines, depending on the fame of the animal.

MacPhee and others worry that the relative appeal of certain animals, especially those known as charismatic megafauna, are distorting our conservation priorities. You might spend millions intervening to stop the extinction of a panda, he says, but “its role may not have anywhere near the significance of some unregarded invertebrate that may be far more important.” These same wondrous, personable big mammals—tigers, elephants, gorillas—are also most likely to be protected in zoos and to have sanctuaries devoted to them. Despite what might be precipitously dwindling numbers in the wild, only a handful of mammal species have been declared extinct this century. “Maybe extinction in that sense has lost its power,” Ladle said. “I’ve often thought that a really high-profile extinction would be the best thing that could happen for conservation.”

All of these scientists agree that human-driven extinction is a crisis. They are not allied with reactionary politicians or climate-change skeptics, and they are all committed to the flourishing of the natural world. But the vitriol of the extinction debate makes clear they see more than statistics at stake.

“If you express a view that’s different to some people, they say you’re anticonservation, and that’s not true,” said Nigel Stork, a conservation biologist at Griffith University in Australia and the author of a 2013 paper published in the journal Science that argued the extinction rate was not as bad as had been previously feared. “Conservation is working. There have been fewer extinctions because we’ve been conserving a key part of the world.”

If anything, the anti-alarmists worry that, in the modern American culture of widespread skepticism about basic science, overstating the facts about extinction could lead to cynicism and attacks from anti-environmental groups—much the way debates over climate models have been spun into anti-environmental rhetoric. “I’m concerned that if we appear to be exaggerating, even if we’re not, even if it’s scientifically based, the difference between documented extinctions and predicted extinctions is so big that people are likely—and justifiably so—to question it,” Ladle said. Hubbell, who was surprised by the vehement reactions to his paper, said that some conservationists have effectively told him, “Damn the data, we have an agenda.”

As the extinction conversation becomes increasingly intertwined with the fraught debate about climate change, the consequences are growing more serious both for animals and for the air, water, and land that surround us. And the swirling controversies demonstrate how even “science-driven” policy can sit uneasily with the workings of science itself. Galvanizing public opinion sometimes demands single dramatic certainties, while science proceeds by estimate, correction, and argument. “The only thing science has going for it is truth and the search for truth,” Hubbell said. “If it loses that, it’s really lost its way.”

Regardless of whose estimates are borne out by future research, few would argue with the anti-alarmists that it’s vital to know what’s really happening as plant and animal populations dwindle around us. “The world is losing species at an incredible rate,” Hubbell said. “We don’t know how fast...but we’d better find out.”

Source:

Here